A MODEL OF LAME DUCK SITUATIONS IN CHANGING ORGANIZATIONS*

Terence C. Krell, Western Illinois University--RegionalCenter

Robert S. Spich, Western Washington University

*An earlier version of this article titled "A Tentative Model of Lame Duck Situations in Organizations" was printed in the Proceedings of the 1992 Conference of the Midwest Society for Human Resources/Industrial Relations, pp 161 175.

ABSTRACT

Change efforts today must take into account the increasing number of lame duck employees created by the turbulent business environment and the resultant early retirements, expected plant closings and widespread layoffs. A model of the lame duck situation in organizations is developed that includes interaction effects with others in the organization, the environment and the organization environment. A three-dimensional attitude construct is hypothesized that explains some of the relevant dynamics and suggests implications for change efforts and opportunities for future research.

INTRODUCTION

Organization change efforts regrettably must acknowledge that organizations do not merely grow, they also shrink. Because of, or in anticipation of, such shrinkage, situations increasingly occur where people remain employed in an organization when it is well known that in a finite period of time their relationship with the organization will be terminated. In the political arena, these people are referred to as "lame ducks," a term originally referring to a holder of public office who has not been re-elected, but still has some of the term of office remaining. In business and public organizations, some examples of lame ducks would be people who are taking an early retirement, those who have given the organization notice of termination, people who are suffering from any kind of terminal disease, people who are creating a family, and people who have been denied tenure guarantees. Furthermore, the lame duck employment condition does not occur only in terms of length of employment, seniority or experience. It applies equally to people who have been long-term loyal employees as well as short term employees with contingent contracts. In general then, the term lame duck can refer to any organizational member who anticipates a fixed date of termination of the employment relationship in the near future. This article defines those people as existing in a lame duck situation (LDS).

In today's turbulent business environment, it appears that the number of lame ducks and the frequency of their creation in organizations is on the rise (Willis, l987). Contributing factors include the increased use of part-time and limited term employment contracts (contingent employees), the creation of early retirement options and computerization of the working place with its subsequent redefinitions of job tasks and roles (American Management Association (AMA), l987). The more recent merger-acquisition trend has created additional lame ducks through the forced joining of incompatible company cultures. This joining often results in redundant job positions, sudden dissolution of organization units and the placement of subsidiaries on the market (Willis, l987). Moreover, the massive layoffs of middle management resulting from the need for increased productivity has exacerbated this phenomenon (Krell & Gale, 1992).

This article proposes to explore themes in the literature relevant to the lame duck situtation. From these themes, a model of the dimensions of human reaction to the lame duck situation is developed, leading to a listing of potentially researchable variables. Finally, the article suggests the implications for change efforts and directions of potential lame duck research.

THEMES IN THE LAME DUCK SITUATION

The lame duck situation (LDS) creates an important organizational issue for a number of reasons. Costs of relationship breaking appears to be the most critical general issue. Since LDS involves a changing relationship, such change imposes (or threatens) certain costs onto the individual and the organization. These costs may be greater than the benefits derived from a continued temporary relationship (Radde, l987). A key management challenge then becomes devising ways to minimize costs and derive continued benefits from the employment relationship (Pascarella, l986). In some aspects it is a game theory situation where management is looking for some optimal strategies for both parties. For example, changing the employment relationship to a nonzero sum game or, structuring a cooperative strategy in a modified prisoner's dilemma format could provide some insights for management of this phenomenon.

LDS highlights how commitment relates to organization effectiveness. Organizational literature at present stresses the importance of the nature and quality of the employment relationship to organizational effectiveness (Margulies & Black, l987). The currently popular "excellence" literature holds the employment relationship as key to achieving an effective and competitive organization (Peters & Waterman, l982). In this viewpoint, individual commitment to the organization remains an implicit central condition for such excellence. Yet LDS would seem to separate this linkage.

In lame duck situations, organizations seem willing to reduce the nature of their commitments to the employees in expectations of certain gains. A counter response in kind from the employee can be expected. But this does not necessarily prevent the organizations from being effective or at least efficient. In fact, the contingent employment practice directly reduces certain direct labor costs for the organization while shifting others such as retirement and insurance to the individual (Pollack, l986). This transfer of costs from the organization to the person is done with efficiency and risk management gains in mind. Yet this is not necessarily a negative outcome to the individual. The employees involved may readily accept the costs of contingent relationships in exchange for higher, direct and immediate income gains, flexible work hours and freedom from organizational entanglements. This may especially hold for organizations where the nature of the work is strongly task oriented and the individuals are less intrinsically motivated. If true, then the centrality of commitment to the "excellent organization" is not a necessary condition in every case for effective organizations.

LDS challenges the humanistic ethos of contemporary human resource management. The dominant view sees people as a renewable, improvable asset, not merely replaceable parts. In this model, people are to be treated as investments to be managed for increased value as opposed to liabilities and costs to be minimized (Weelock, l985). Yet LDS seems to challenge this viewpoint head on as the employee approaches the end of his/her job tenure. Instead of the positive virtues of humanism, the individual increasingly represents potential negatives for the organization : people may contribute less than they receive causing an imbalance in the basic Inducements- Contributions equation for organizational stability (Simon, 1965).

Individuals can become a liability to the organization when their behavior affects important external relations as in the case of a sales rep. LDS means they are replaceable. The nature of the job may becom intolerable: a person's linkages with others are minimized; roles are reduced ; job scope may be limited to simpler ,repetitive and less riskier tasks ; job responsibilities are reduced .

Despite the organization's best efforts to put on a human face in dealing with the LDS, the underlying reality may be more basic and the motives more calculating. Services like outplacement may really be control strategies. They reduce the risk of abnormal employee responses to a lame duck situation through monitoring, focusing and directing behavior away from the organization (AMA, l987). This Machiavellian interpretation is less cynical than realistic considering the basic economic nature of the work organization. Because LDS poses a challenge to the ingenuity and perhaps the integrity of the human resources function, it seems an important phenomenon to study.

Finally, LDS is interesting because it is about unfitting or de-fitting the person from the organization. It essentially represents the reversal of the standard "fit" model. A person can experience depersonalization of their relationships with the organization. Reverse socialization and de-acculturation may be taking place as the organization must increasingly discount the value and presence of the individual. The Gold-Watch Dinner and the retirement party may not be so much the "last thank you" as much as a way for the organization to symbolically "de-memberize" a person. Functionally, this ritual is the opposite of the workshop that welcomes the new employee.

In summary, LDS is important because it is essentially about relationship breaking. In a sense, it is about organizational telos. LDS is essentially a reaction to finality and endings. Because breaking relationships is a social phenomenon, LDS involves individual psychological processes as well as social ones.

A MACRO-THEORY FOR LAMEDUCK EMPLOYMENT SITUATIONS

The above review of relevant themes suggests that a large number of separate literatures in social psychology , management and economic theory that could provide some theoretical understanding for the lame duck phenomenon. The complicated nature of LDS suggests however that only an eclectic review of the appropriate literatures makes sense. Theoretical developments in attribution processes , equity, exchange and small group socialization process no doubt provide some further explanatory basis for the lame duck phenomenon. Research on agency problems, organizational justice, and job design likewise capture some other aspects of this phenomenon. The most probable relevant literature comes from research interested in turnover in organizations, especially that which deals with the issue of volition in separation from the organization. This varied literature demonstrates the complex nature of the LDS.

While no formal theory of lameducks has been developed, speculative theory suggests that the rising intensity of competition (Porter,1980; Kantrow, 1983; Peters, 1988) along with confounding environmental conditions (Terreberry, 1968; Pfeffer, Salancik and Leblebici, l978; Lindsay and Rue, 1980) have combined to create particularly difficult "employing" situations in organizations. Management finds itself increasingly under pressure to remain "competitive" and to manage for optimum "competitiveness" of the organization. Environmental pressures are diverse, multiple and changing. Increased complexity, uncertainty, risk and interdependence seem to be the basic reigning conditions for management decision making. Strategy-making under these difficult conditions tends towards the adaptive mode where decisions reflect the outcomes of political struggles as the organization reacts to problems in an incremental and disjointed way while it adapts to these environmental conditions (Mintzberg, 1973).

Given these conditions, managment might tend to want to reduce its long term liabilities and risk of exposure to a fixed position in the marketplace. Maintaining flexibility of response, "lean" organizations, control over the less predictable organizational elements and processes, and preparedness for sudden and wholesale movement of whole subunits (eg. moving manufacturing abroad) all suggest that the employment of the human factor could come to be seen more as a liability than as asset. Since people are less adaptive than capital or equipment, substitution of the latter for the former may come to be seen as a natural decision. If substitution is not possible, minimizing the linkages with people in terms of organizational committments and responsibilities may be a second "natural choice" of the pressured manager. One theorized outcome of this scenario is the lameduck. Employment situations which reduce management exposure, minimize committed resources and increase flexibility of response might be favored over the longer term human resource management models in traditional domestic and foreign firms. The lameduck, as described in this paper, represents the increasing result of such a choice option.

NATURE OF LDS

Present knowledge of LDS comes from observation of common experience. The lame duck situation exhibits some specific characteristics. However, each LDS represents a relative and not an absolute condition because any one LDS possesses differing degrees of these characteristics. First, the changed nature of the employment committment is a commonly known fact. People are expecting an end to the relationship. Second, "lame duckness" can be a characteristic of either the person, the position/job category or both. You can eliminate a job classification as well as lay a person off from work. Third, LDS alters the person's role in the organization . Role change may result in a lessening of job responsibilities, increasing ambiguity of expectations that can be legitimately held, increasing tenuousness of attachment to organizational units and emphasizing the obvious -- the person's irrelevance to the organization's future . Fourth, the individual's power tends to decrease. They have a lessened claim to resources , priviledge and people's time. While formal authority of position may be there, the person's influence in decision-making probably decreases.

Finally, the LDS time frame is dynamic. Traditionally the lame duck period had a relatively fixed ending date, in the very near term. Lame ducks were infrequent and the duration of their stay ranged from the two weeks to two months resulting from courtesy in giving notice. Very often these periods were a matter of form, and the individual was politely escorted from the organization with compensatory pay in lieu of additional work. Today, however, lame ducks may remain in the organization for much longer periods of time. For example, a person may be asked to "stay on" until a project is complete even if there is no clear ending date to the project. No doubt there are additional attributes of the lame duck circumstance which further research will discover.

THREE CRITICAL ISSUES

The lame duck situation raises three issues about our understanding of the traditional employment contract, tacit and otherwise. The first major issue focusses on the effects of LDS on both the individual and the organization . Second, we want to understand better what factors determine whether or not the lame duck relationship will remain functional or turn dysfunctional for either the individual or the organization. Last, there is the question of whether or not there is an optimal way to work out this relationship. Given a known end horizon to the relationship, there are temptations for both management and the employee to seek out purely self-interested solutions of the modus vivendi.

Figure 1 shows a schematic model of LDS effects. Besides the internal effects on the employee, all internal work relationships as well as some key external ones are potentially subject to the fallouts of a LDS decision.

The effects of LDS will probably fall more heavily on the individual lameduck than on the remaining members or "survivors", mostly because the lameduck experiences LDS as a highly personal, idiosyncratic and holistic experience. The organization, in contrast, experiences the separation as a partial experience. The lame duck "loses" the entire organization and the web of relationships and experience gained over time. In contrast,co-workers, bosses and subordinates only lose one person and not an entire experience of relationships. They have others to interact with once the lameduck is gone. Their "losses" are mitigated by the continuance of organizational life: there is a job to be done on Monday morning. This observation that "life goes on" recognizes the simple fact of organizational inertia and how the meaning of organization involves a totality of elements.

Figure 1 simply identifies key relationships that probably have an impact on the LDS response. Details of these effects need to be more clearly defined . Furthermore, their interactive effects may have to be netted out. Positive interactions with co-workers may cancel out negative effects of subordinate reaction. Thus the response to LDS might require a measurement of a network of responses and not just the individuals reaction.

PROPOSED MODEL FOR LAME DUCK RESPONSE

LDS As an Attitude Construct

We propose to treat LDS as an attitude construct with three dimensions (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). It involves a perceptual dimension which essentially deals with personal sense-making of the situation. People need to explain their situation with a set of beliefs, and assumptions structured as a theory to explain the fact of their own job demise, how it came about and what it means. LDS has an affective dimension which is emotionally charged. Breaking relationships often involves complex emotions and feelings of strong likes and severe judgments. Powerful values come into play which provide guidance on the appropriateness of thoughts, feelings and actions. Finally, LDS has an action dimension which describes intended and executed behavior.

The behavior of interest is the individual's response to their lameduck situation. This behavioral category involves sets of actions rather than a single action. Behavioral categories as such cannot be observed. Instead they are inferred from single actions that are assumed to be instances of the general behavioral category (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). The particular behavioral responses are actions that have a target and occur with a context and time frame which change.

We must also note the relationship between behavior and its antecedent intention in the measurement of the response to LDS. Intentions are like behavior in that they consist of actions, a target for the action (an attitude object), a context and time elements. Intention corresponds to behavior the more similar their elements are. Since prediction of the response to LDS is of interest, knowledge of intentions should improve our understanding of the types and probabilities of LDS behavioral responses. This depends in part on the stability of intention over time and the effects of moderating variables as seen in Figure 1.

As an example of how a moderating variable can affect intentions, we can look at the case of direct experience. Peoples intentions about how they would act to a LDS, without direct experience of LDS, will probably change once they become lame ducks. In contrast, people who have been a lame ducks will more than likely have developed more realistic expectations about LDS and their intentions will probably be more stable over time. Common experience about peoples attitudes towards unemployment, being fired or homelessness shows similar development.

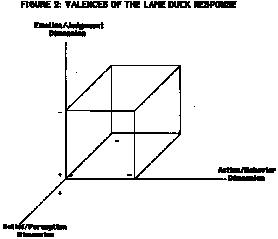

Categorical Responses as Behavioral Categories

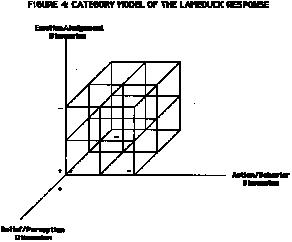

Lame Duck Response (LDR) is our term for the individual's response to existing in a lame duck situation. The initial model of the lame duck response, as proposed here, is categorical in nature, that is, the responses are depicted as distinct types of reactions or behavioral categories as defined above. Although it is possible that the response categories may appear on a continuum (single dimension) or a matrix (two dimensions), it seems more likely that they are related through multiple dimensions. Thus, the proposed model is a three-dimensional attitude construct, where the LDS is a composite reaction in a multidimensional space. Each dimension described above is itself composed of a number of variables. Future research may well find it appropriate to handle each of these variables separately in a multidimensional space. The dimensions of the model can be seen in Figure 2.

As part of the overall attitude construct, the dimensions represent composite variables. They are composed of a subset of reactions to the changing employment relationship. For example, the belief/perception dimension represents cognitive reactions to various aspects of the changed job relationship. The content of these reactions is the facts of the situation that have become salient to the individual. They are the beliefs and assumptions that go into a personal theory that explains the person's situation to herself and others. This content is the "stuff" of personal and organizational "sense-making."

The choice of the variables for each dimension, at this time, is a matter of judgement based on experience and a limited focus group technique. The variables in Tables 2A, 2B and 2C represent some key aspects of the employment relationship needed in sense-making.

For the belief/perception dimension, concerns about equity, finality, justice and justification, power-dependence, costs (magnitude and sharing), the discounted future, personal responsibility and locus of control seem appropriate variables to focus on. Each belief represents a depiction of events that is either in agreement or disagreement with the formal organizational view of LDS events.

The emotional/judgement dimension is equally complex. Just as beliefs affect perceptions,in this case, emotions are seen to have a direct effect on judgement. Here, judgement is the outcome of a fixing of emotional reactions in positive and negative modes. People eventually come to express their emotions in a judgement about other people and towards the formal organization. Key emotions thought to play a role here are negative/positive expectancy (fear, hope, anxiety), identification (as empathy, sympathy and antipathy), liking (attraction, support) guilt, anger and satisfaction (happiness, sadness). Each emotion represents a feeling about events ending in a judgement that either approves or disapproves of the LDS situation and its antecedent events. Since LDS represents a breaking of relationships, the Kubler-Ross cycle of mourning may provide some guidance in the selection of the most appropriate emotional variables.

Finally, the action/behavior dimension consists of the expected set of behaviors that an individual can demonstrate within the LDS circumstance. This dimension is complicated by the large repertoire of actions available to the person and the multiple attributes of each action. Actions can be differentiated in terms of intention, precision/discipline of execution, effort and resource requirements, linkage to effects (direct-indirect), degree of self-focus, timing and expected outcomes. Each action represents a behavior that results in outcomes which represents either a gain or loss for the individual.

Each dimension's variables are presented here as statements with a positive or negative valence switch. Thus, each dimension has an overall valence measure which is the aggregate of the valences of the individual variables. In research practice, the valence switch pairs could serve as opposite ends of a Likert scale. The appropriate weights of each scale could be determined and the details of the dimension constructed from interview and survey data.

TABLE 2A

BELIEF/PERCEPTION

LD/organization initiated termination decision.

The termination decision was/was not equitable/deserved.

The termination decision is final/can be changed.

The termination was/was not the LD's desired outcome

The termination was/was not the organization's desired outcome

The termination rationale was/was not justified/appropriate.

The termination decision will/will not create hardship for LD.

LD continues to need/not need organization's benefits/resources.

The termination will/will not significantly affect the future.

TABLE 2B

EMOTION/JUDGEMENT

LD is looking forward to/dreading termination.

LD expects/does not expect future relations with organization.

LD identifies with/does not identify with organization.

LD likes/dislikes the organization

LD likes/dislikes co-workers

LD is satisfied/dissatisfied with the procedure of termination

LD blames/does not blame colleagues, self, organization for the termination decision.

TABLE 2C

ACTION/BEHAVIOR

LD engages /does not engage in behavior detrimental/beneficial to organization.

LD acts/does not act in similar manner to previous status.

LD interacts/does not interact with co-workers in manner similar to previou status.

LD actions damage/helps self.

LD demonstrates more/less initiative, effort, discipline, concern

MODEL AND ILLUSTRATIVE CATEGORIES

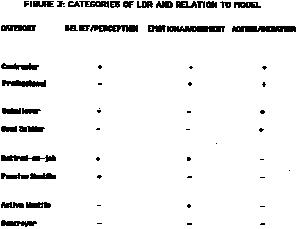

In the simplest form, each dimension develops a positive and negative end, from the net valence. For example, if the majority of the variables on a dimension are negative, then there is a negative net valence. Thus, we derive Figure 2. This figure shows the dimensions with the axes labelled as positive or negative valences. The three dimensions, with two valences give eight combinations or categories for LDS. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

We have given a name to each category for illustrative purposes. The name suggests the character of each category as derived from the net valence on each dimension. Each category represents a multidimensional space in the model shown in Figure 4. Note that the categories fit into pairs, where the members of each pair differ on only a single dimension. Both members of each pair always share the dimension action/behavior.

The Contractor and the Professional

These two categories differ primarily in the belief/perception dimension. Both essentially ignore the limited term/nature of the relationship and act as if the relationship will last forever. The contractor believes there is the possibility of continuing the relationship in some way, perhaps through consultation, part-time employment, or contract renewal. The professional, however, expects to be gone at the end of the lame duck period. Both continue to give their best efforts to the organization, and do not express any negative feelings.

The Unbeliever and the Good Soldier

These two categories differ primarily in the belief/perception dimension. The unbeliever and the good soldier differ from the contractor and the professional primarily in the affect or emotion they hold toward their lame duck situation. Both are very concerned over the coming termination and have negative feelings about the situation. Both continue to do their jobs to the best of their ability. They differ primarily in their motivation; the unbeliever doesn't really believe the termination is going to occur, as if by somehow working harder the decision will be reversed; the good soldier understands the realities of the situation, and continues working out of pride or because it is expected.

Retired-on-the-Job and the Passive Hostile

These two categories differ primarily in the emotion/judgement dimension. They differ from the previous four categories in the action/behavior dimension in that they may engage in or allow to occur behaviors having a negative effect on the organization. Both tend to believe the relationship will continue, perhaps through a pension, a good reference, or part-time employment because of some special expertise. Both perform work to the minimum levels required by the organization but not beyond. They believe the organization has no real power to punish them. Retired-on-job doesn't mind the expected termination and may actually be looking forward to it favorably. Passive hostile is angry, and although he will avoid active destruction, he will delight in opportunities to cause damage through omission.

The Active Hostile and the Destroyer

These two categories differ primarily in the emotion judgement dimension. They differ from retired-on-job and the passive hostile primarily in their belief about the possibility of a continuing relationship with the organization. Both feel they have nothing to lose by any damage they can do to the organization. They differ in that the active hostile is not angry about the situation, he is merely apathetic or willing to take the opportunity to "get even" as it occurs. The destroyer, however, has no good feelings remaining and may actively seek out opportunities to damage the organization, perhaps through selling trade secrets, hiring incompetents, or making unfavorable contracts.

IMPLICATIONS OF LDS FOR CHANGE EFFORTS

Not all lame ducks will repond to LDS in the same way. Many of them can remain useful members of the organization long beyond the time when cautious managers would have them removed from the organization. Expansion of the concept of lame ducks in the minds of those remaining in the organization can assist all concerned in understanding and dealing with LDS and may well assist in developing a more satisfactory transition for all concerned.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCHING LDS

Researching a complex phenomenon such as the lame duck response requires a disciplined research strategy. Even though the lame duck phenomenon is a directly observable event, it requires certain conditions to be a researchable organizational issue. It first needs an accepted vocabulary for the labelling and description of the variables. And it needs a basis on which to differentiate it from other organizational phenomenon either through theory or method of research. The relevant variables described above will need to be further identified, clarified and simplified. Thus description is the first goal of the strategy.

One way to achieve this would be to conduct open-ended interviews with appropriate sample groups to better articulate the meanings they give to the lame duck experience. For example if a faculty group which was denied tenure were the population chosen, we would conduct interviews with them based on the model dimensions to tease out the salient variables. The respondents would be asked questions about their perceptions, feelings and behaviors with regard to the lame duck experience. From these interviews, key variables would be identified that could serve as the basis for a survey of a subsample the target population. A factor analysis of these subsurvey results could then provide the basis for the development of Likert type scales. Alternatively, the variables described in Figures 2A, 2B and 2C lend themselves to immediate construction of such scales. We recommend the former approach.

The second part of the strategy would involve the use of these scales to test for the validity of the category model. By combining the results of the scales on a by dimension basis, the three-dimensional model could be constructed from categories along each dimension or from the net valences. Such an approach would allow more precision in identifying categories of LDS.

An extension of the test for model validity might involve a survey of a larger population using a multidimensional scaling methodology. A mapping of individuals in three-dimensional space, consistent with the model, could then be used to "test" the validity of the original model. It is expected that the model would need to be modified according to the results.

Another research activity could be to identify the intervening variables that affect the nature of the LD response. Several types of variables are expected to play a role in the variance of response. Organization environment context variables may be one such important influence. Professor response may differ from lawyers may differ from advertisers because of the nature of their respective businesses. If and how those differences translate into differentiated responses will be a question of interest.

A second intervening variable may be personality. Observers of human behavior are continually surprised by the behaviors people demonstrate in contrast to expectations held about them. Professors can be petty, nasty people just as bus drivers can demonstrate heroic behavior. It is often the unknown "personality" variable that determines the response to a situation. In like manner, personality may be the major determining factor in the types of LD responses.

Underlying such research activity is an effort to develop a theory of the lame duck response. Since description, prediction, and prescription are the goals of organizational science, we would hope that this effort leads to a better understanding of the lame duck phenomenon so that it can be managed better for the long-term benefit of the individual and the organization. In the meantime, the more meager and humble goal of just understanding the LDS will remain the focus of our own research.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Management Association. (1987). Responsible reductions in force ., New York: N.Y.

Ajzen, Ice, and Martin Fishbein , Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior , 1980, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs N.J.

Dwyer, G.E. (1987, May 4). "Post panic strategy for the displaced executive". Industry Week , 233, 14.

Kantrow, Alan M. (ed.) (1983) Survival Strategies for American Industry , John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Krell, T. C., and Gale, J. "Societal Impact of Information Technology Induced Change on Middle Management in the 1990s" Proceedings of the First IFSAM Meetings , Tokyo, Japan September 9-12, 1992

Lindsay, W.M., and Rue, L.W. (September,1980) "Impact of the Organization Environment on the Long- Range Planning Process: A Contingency View" Academy of Management Journal Vol 23: pp.355-404

March J.G. and Simon, H.A., Organizations New York, John Wiley 1958

Margulies, N., & Black, S. (1987, Fall). "Perspectives on implementation of participative approaches". Human Resources Management , 26(3), 385-412.

Mintzberg, Henry, (Winter, 1973) "Strategy-Making in Three Modes", California Management Review XVI, no.2

Pascarella, P. (1985, August 19). "Bitter lesson of early retireement; No job guarantee for executives"., Industry Week , 266(1), 7.

Pascarella, P. (1986, July 7). "When change means saying 'you're fired'". Industry Week , 230, 47-49.

Peters, T. J., & Waterman, R.H., Jr. (1982). In Search of Excellence . New York: Harper and Row.

Peters, T.J. (May, 1988). "Restoring American Competitiveness:Looking for New Models of Organizations" Academy of Management EXECUTIVE pp 103-110

Pfeffer, J., Salancik, G.R., and Leblebici, H. (1976) "The Effect of Uncertainty on the Use of Social Influence in Organizational Decision Making.", Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol.2 (June):227-244

Pollack, M.A. (1986, December 15). "The disposable employee is becomming a fact of corporate life." Business Week , 52-54.

Porter, Michael E. (1980) Competitive Strategy , The Free Press, N.Y.

Raddle, P.O. (1987, January). "Dealing with employee status deprivation". Training and Development Journal , 40, 61-64.

Terreberry S. 1968. "The Evolution of Organizational Environments." Administrative Science Quarterly 12:590-613

Weelock, K. (1985, March). "No fault corporate divorce". Personnel Administrator , 30(5), 112-116.

Willis, R. (1987, January). "What's happening to America's middle managers?" Management Review , 76, 24-33.